Polygon moduli spaces

Summary:

The moduli space of polygons encodes how many ways you can bend the edges of a 3D polygon, ensuring the distance between adjacent points remains the same. In this talk, I gave people physical models of polygons, and had them figure out the moduli space up to rigid rotations. This reveals quite a lot of deep structure. Symplectic geometry, coadjoint orbits, toric geometry, and quiver varieties all come into play. We can even reframe the moduli space gauge theoretically as that of some flat connections on the punctured sphere. This web of equivalences make polygon spaces useful testing grounds. This is amplified when we pass to their hyperkahler analog, the hyperpolygon space, who connects with Nakajima quiver varieties and the moduli space of Higgs bundles.

Presented at:

- UC Berkeley geometric represenation theory seminar, Spring 2023

Polygon moduli spaces

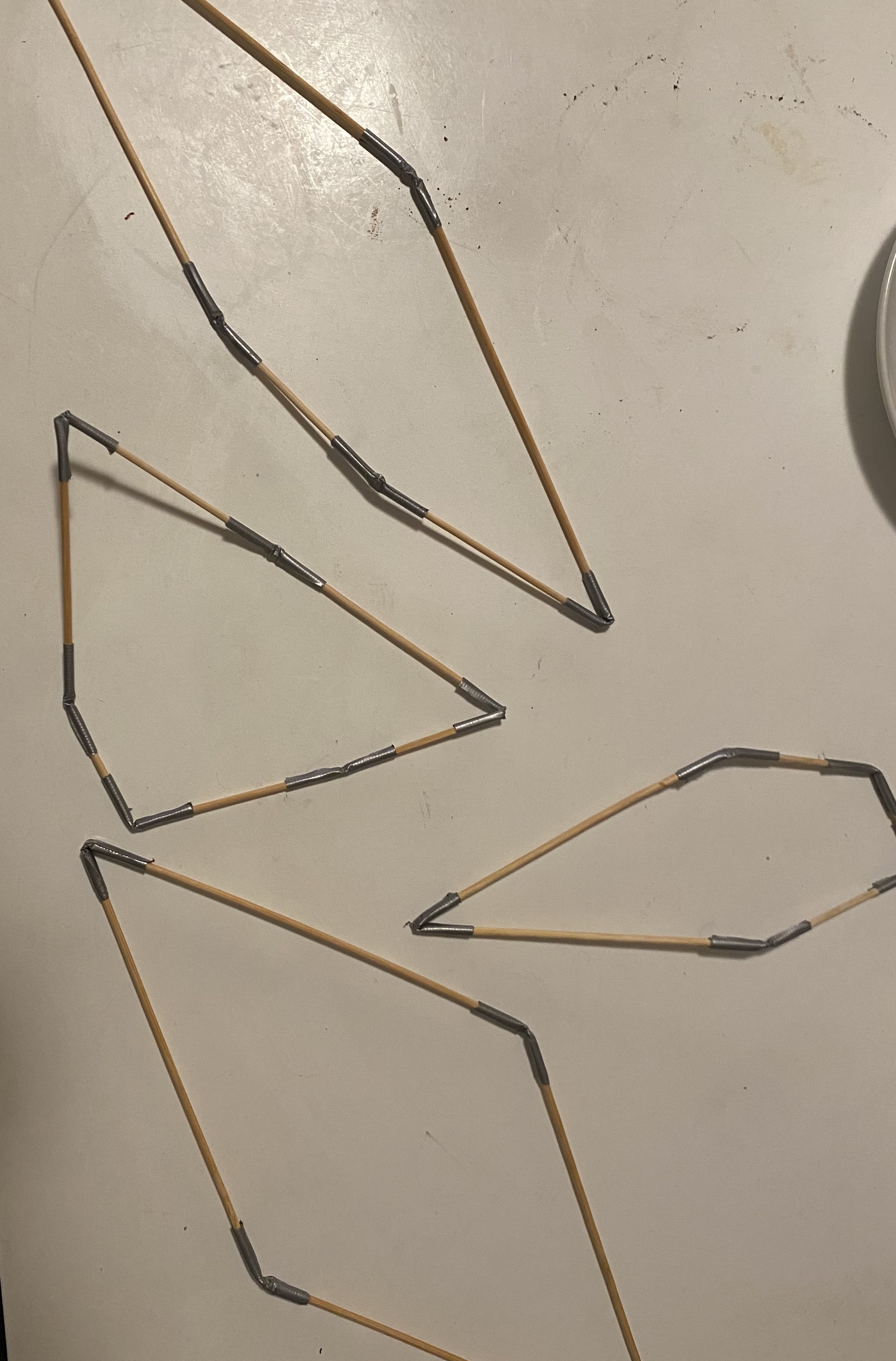

A polygon with specified edge lengths is a collection of points in 3 dimensional space such that the distance between two connected points equals the specified edge length. What is the moduli space of these configurations, up to rigid transformations? What is its topology? This is a very concrete question, because you can physically build and play with these polygon. All you need are

- Skewers (or any small stick)

- Duct tape Simply cut the skewers to the desired length, hold the sticks tip-to-tail (but not quite touching), and tape them together. The joint is suprisingly flexible and durable. With a few minutes of arts and crafts, you can have an army of polygons to play with!

|

|---|

| Some of my polygon friends |

I gave a somewhat impromptu talk where I handed everyone some of my homemade polygons, and had people reason through the following few questions.

- Question: What is the moduli space of a triangle with specified edge lengths?

- Answer: Zero, any two such triangles are the same up to rotation

- What about a quadrilateral?

- Generically, it’s 2 dimensional

- What about a pentagon? an n-gon?

- counting equations and degrees of freedom, it is (generically) 2n-6.

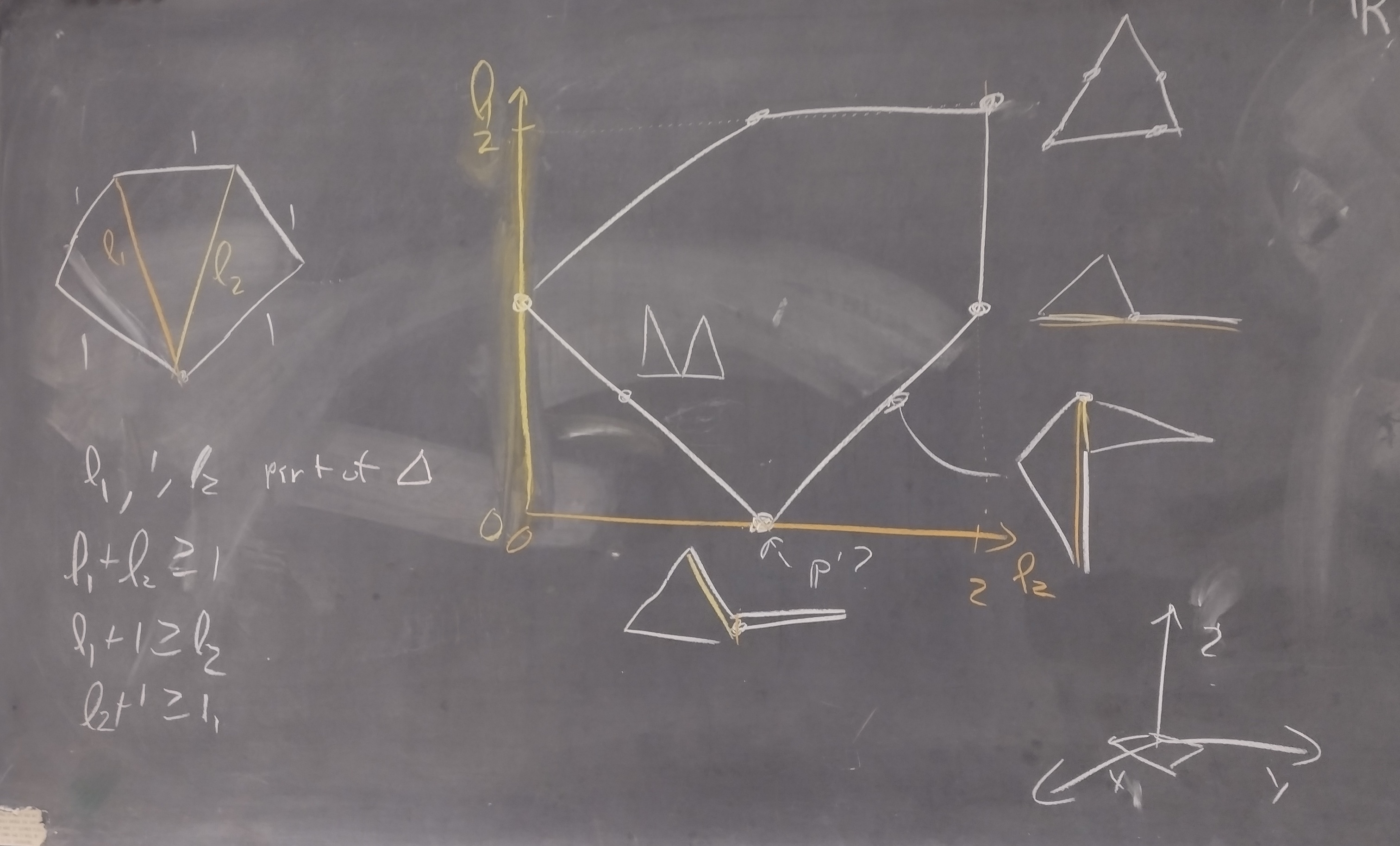

- What is the moduli space of a quadrilateral?

- This one is much trickier if you can’t play around with it. There are two possible angles, the angle at a specified vertex, and the dihedral angle bending the quadrilateral across the opposite diagonal. The radius of the dihedral angle circle changes with the vertex angle. In fact, for the two extremes of the vertex angle, all dihedral bending are equivalent. Thus, the circles pinch to points, and the moduli space is a sphere.

Symplectic geometry

What is the geometry of the moduli space of an n-sided polygon?? You can very naturally think of the moduli space as a symplectic manifold. It arises from the product of n spheres $(S^2)^n$ (the nth sphere describing the direction of the nth side). This has a symplectic structure, where the radius of each sphere is the length of the corresponding edge (see my blog post on symplectic and toric geometry for the symplectic structure of $S^2$) We need all the edges to close up, and to mod out by rotations. Turns out, we can do both at once with a Symplectic reduction.

Consider the group $SO(3)$ acting on polygons by rotation. This individually rotates each sphere in $(S^2)^n$. As I described at the very end of my post, the lie algebra $\mathfrak{sl_2} \cong \mathbb{R}^3$ of $SO(3)$ can be identified with 3D euclidean space. Acting on the sphere effectively sits $S^2$ at the origin of the dual $\mathfrak{sl_2}^\ast\cong \mathbb{R}^3$. The moment map sends each point of $S^2$ to a point in $\mathfrak{sl_2}^*$, namely the point itself! The moment map on a product of manifolds is the sum of the individual moment maps, so the total moment map $\mu$ of $SO(3)$ acting on $(S^2)^n$ is just the sum of the corresponding points on each of the spheres (which are scaled to the length of the edges). That is, it is the sum of all vectors in the polygon. For the polygon to be closed, we need a point in the configuration space $(S^2)^n$ to have $\mu=0$. Now we take the symplectic reduction \((S^2)^n//SO(3) = \mu^{-1}(0)/SO(3)\) which canonically produces a symplectic manifold. But, the right hand side is the space of closed polygons up to rotation, or the $n$-gon moduli space! Therefore, we have a natural symplectic structure. In fact, this structure is Kahler, owing to the Kahler structure on $S^2$.

Toric structure

These polygon moduli spaces carry many more rich structures. For one, these are toric symplectic manifolds. That is, there is a half-dimensional torus action rotating the manifold, which preserves the symplectic form and has isolated fixed points. This lets us form nice “action-angle” coordinates of the manifold, which encode the angle of the torus and the value of the moment map of the torus rotation action. We already saw the toric structure with the quadrilateral, where the $S^1$ action was dihedral rotation around the diagonal. The action coordinate is the length of the diagonal (which we encoded with the vertex angle). That is, the length of the diagonal is a function on the moduli of quadrilaterals $S^2$, and its hamiltonian vector field generates the $S^1$ action bending the quadrilateral along the diagonal. (this is like rotating the sphere-shaped moduli space).

In an n-gon, the torus action comes from dihedral bending on the $n-3$ missing diagonal edges, and the moment map measures the length of these diagonals (See Kapovich and Millson, The symplectic geometry of polygons in euclidean space). Its lots of fun to physically make a pentagon, play around with it, and graph the possible lengths the two missing diagonals. They trace out a convex 2D polygon, which is exactly the toric diagram for the polygon moduli space!

|

|---|

| Diagram of the possible diagonal lengths for an equilateral pentagon. This is the toric diagram for the 4 dimensional moduli space of configurations of this polygon |

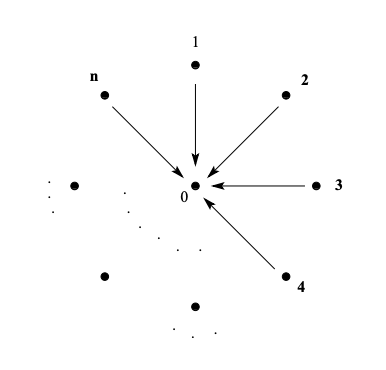

Quiver varieties

These polygon spaces serve as the concrete realizations of even fancier ideas. For example, you can represent the direction of each stick as a point in $S^2 \cong \mathbb{CP}^1$, or as a 1-dimensional complex subspace of $\mathbb{C}^2$. The polygon moduli space is a collection of $n$ 1-dimensional subspaces of $\mathbb{C}^2$, up to linear transforms $SL(2,\mathbb{C})$ of $\mathbb{C}^2$. (This is a manifestation of the Kampf-Ness theorem: The symplectic reduction by the real group $SU(2)$ is the same as simply quotienting by its complexification $SL(2,\mathbb{C})$). Let’s draw the vector spaces in the above construction: Represent each vector space by a node, and connect them by an arrow whenever one maps to another. This is called a quiver.

|

|---|

| Star-Shaped quiver |

Here the middle node has dimension 2, while all the outer ones have dimension 1. This is called a Star shaped quiver, for very reasonable reasons. The polygon moduli space are the first example of a Quiver variety! I spent a good while this semester trying to understand quiver varieties, in the context of Coloumb branches.

Polygons as vector bundles

With quivers, we identified each polygon with a bunch of points on $\mathbb{CP}^1$, each with an associated length. Let us recontextualize this, using gauge theory. Each stick is a translation by an element of the lie algebra $\mathfrak{sl}_2$ which we associate to each missing point. We represent this data as monodromy around a puncture in $n$-times punctured $\mathbb{CP}^1$. By the Riemann-Hilbert correspondence, we can always cook up some rank 2 bundle on the punctured sphere with the perscribed monodrom. From an $n$-gon, we get a flat vector bundle on a $n$-punctured sphere. The condition that the polygon is closed states that the sum of all monodromies must be zero. But, this is already enforced from the group structure of the fundamental group of the $n$-punctured sphere!

With this correspondence, the moduli space of polygons in actually an open, dense subset of the moduli space of such flat bundles. Now we can learn about these moduli spaces of connections, which everyone cares about, using polygons! for example, Kapovich and Millson realized the torus action (Described above) coincides with the almost-toric action of Jeffery and Weistman.

Hyperkahler analouge

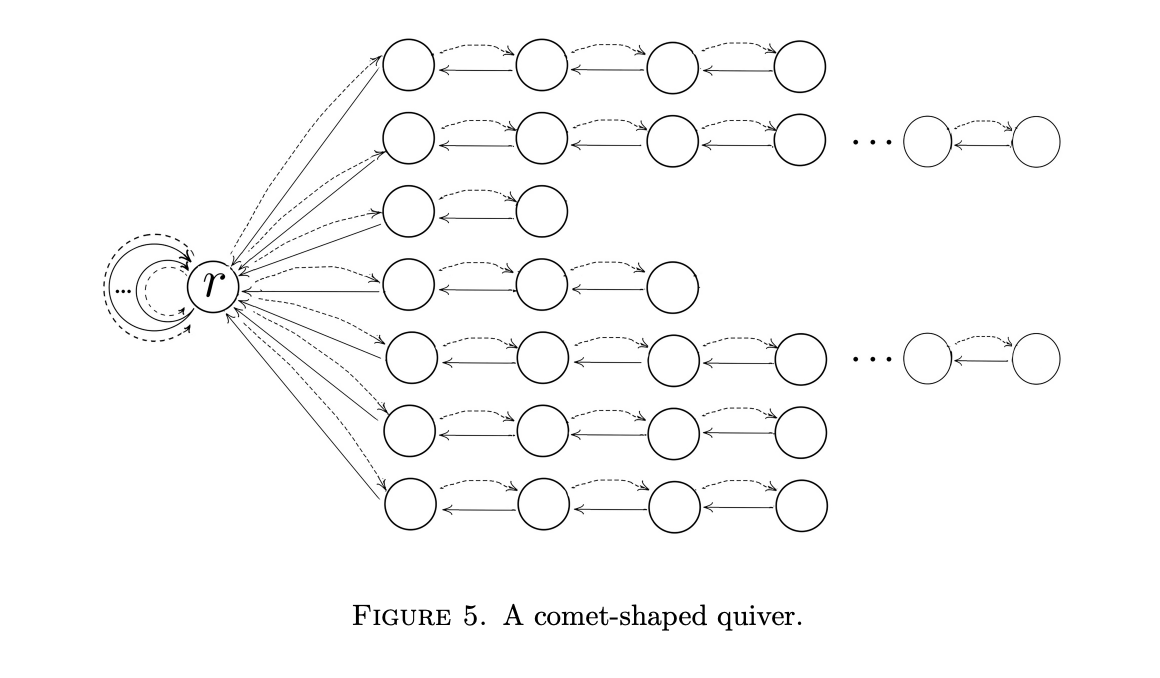

Things get truely useful when we complexifying the quiver, by including backwards arrows. These are maps that go back from the two dimensional central space to the sattelite one-dimensional spaces. The resulting quiver variety is called the nakajima quiver variety. The ordinary quiver variety, the polygon moduli space, is Kahler, but this new space is Hyperkahler. The new space locally looks like the cotangent bundle of ordinary quiver variety. Globally, where a Kahler manifold is complex, a hyperkahler manifold is a complexifed complex numbers, the quaterionions. We call the new variety the hyperpolygon space, because it is a hyperkahler analoug of the ordinary polygon space.

Hyperkahler manifolds are hard to understand. These hyperpolygon spaces are a nontrivial example we can really get our hands on, the perfect testing ground. It has gotten much attention, like in Proudfoot’s work (e.g Hyperpolygon spaces and their cores).

Remember how polygon spaces were secretly moduli of bundles over a punctured sphere? If god is nice to us, hyperbolygon spaces should be the complexification of the moduli of vector bundles, which is called the moduli space of Higgs bundles. It is a blessed day, because that’s exactly what happens! We can generalize this to vector bundles and Higgs bundles over higer genus surfaces by adding loops to our quiver. Instead of being star-shaped, it becomes comet shaped. (See Rayan and Schaposnik, Moduli space of generalized hyperpolygons)

|

|---|

| Comet-Shaped quiver |

All together, the moduli space of polygons is a very concrete object which can be understood in many different ways. It’s generalizations are some of the core examples of hyperkahler manifold. With them, we can better understand some of the more intrensically interesting hyperkahler manifolds, like the moduli space of Higgs bundles.