Spherical stick bombs

Summary:

Woven popsicle sticks store a large amount of elastic energy, held together by only friction. When thrown, the sticks can explosively fly apart, creating a stick bomb. Must stick bombs lie in a plane? Could you weave sticks along the surface of a sphere, making a rigid object without glue or bindings? What if you drop it?

On the Illistrating math discord server, there was discussion about a very dramatic model at ICTS.

|

|

|---|---|

| Large woven Geodesic ball at ICTS |

It’s made from bamboo slats, held together by zip ties

|

|

|---|---|

| Close up of a single vertex of the Geodesic ball at ICTS. (picture thanks to Katherine Strange) |

Do we need the zip ties? Perhaps we can weave the bamboo slats, held together by pure force of will.

This reminds me of stick bombs!

This question brings me back to a childhood goof-off activity. Take a few popsicle sticks, and weave them together, and you get something surprisingly rigid. When properly woven, each stick alternates over and under and over, forced to bend around the other sticks. But wood wants to be straight. The elastic forces press the sticks tightly against one another, and their friction holds the entire ensamble tight. You can wave the whole business around using just one stick, not glue or anything!

|

|---|

| Some examples of stick bombs |

Throw your woven sticks against a wall, and the weave explosively unravels. The elastic energy releases all at once, the sticks fly everywhere, and congratulations you’ve made a stick bomb. Some stick bombs are especially potent, and unravel with a single stick remove. The combinatorics behind stick bombs is surprisingly addictive, and feels deep. (I wrote a bit about this here.

Now for today’s question: Must a stick bomb be planar? Can I make something like the ICTS model using stick bomb design principles?

Perhaps counterintuitively, I don’t see an issue with a non-planar stick bomb. Instead of weaving the sticks on a 2D plane, we can weave them along the surface of a sphere. Topologically the weaves are identical: A sphere with a point missing is topologically indistinguishable from a plane. The difference is geometric, the spacing between crossings and the length of sticks. The existence of non-planar stick bombs is not up to math, but to physics: Could a spherical stick bomb still hold together under friction alone?

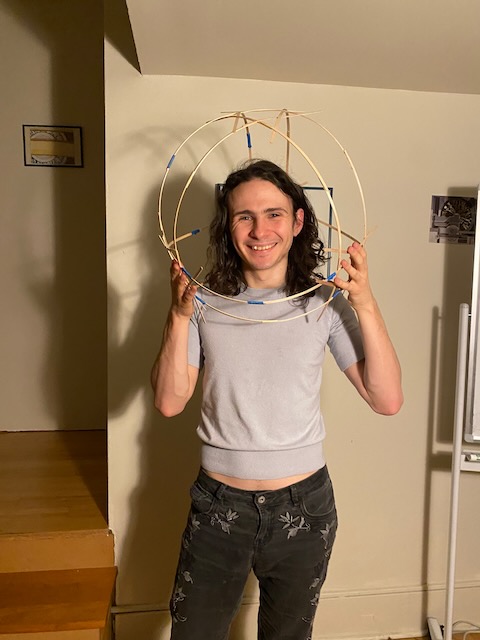

This is fairly large – it has to be, or the sticks would snap (see the construction process below). Makes a good space helment.

|

|

|---|---|

| I’m an astronaut |

The design

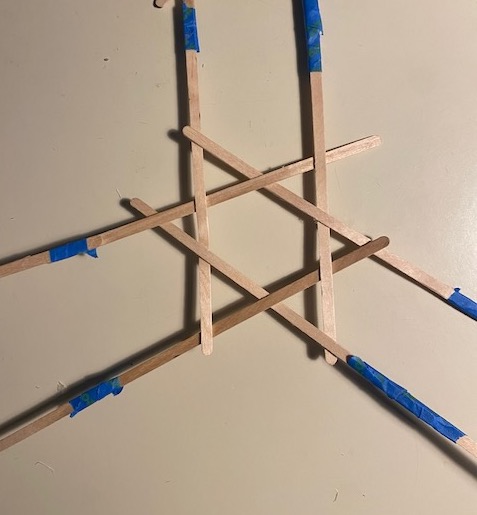

My critter is a built from a tetrahedron. Each edge is made of two parallel sticks, and three edges are woven together at each vertex. The weave is based on the Kagome pattern. Here’s one vertex, done in pipe cleaners: You can see that the yellow edge is above the purple edge, the purple is above the red, and the red is above the yellow. The cyclical ordering ensures every edge is clamped above and below by another. Also, the crossings around every edge alternate over and under. I wrote a little about the mathematics of weaving and other pipe cleaning crafts here.

|

|---|

| Each vertex of the tetrahedron is woven togehter in a Kagome style, shown here in pipe clenaers |

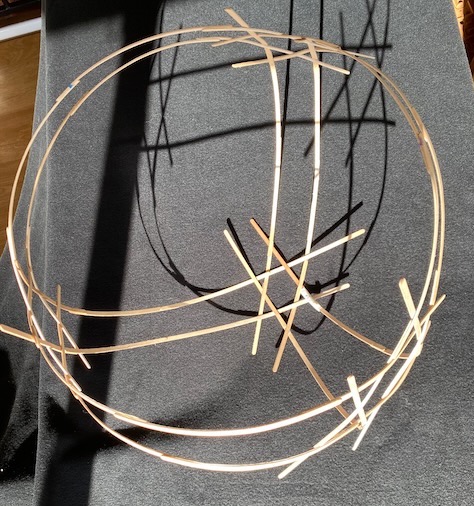

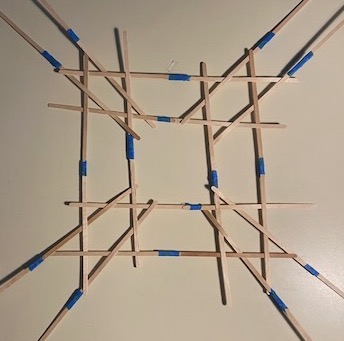

Already a single vertex rigidly holds the three edges in place. Here’s what it looks like in popsicle sticks:

|

|---|

| Each vertex of the tetrahedron is woven togehter in a Kagome style, shown here in pipe clenaers |

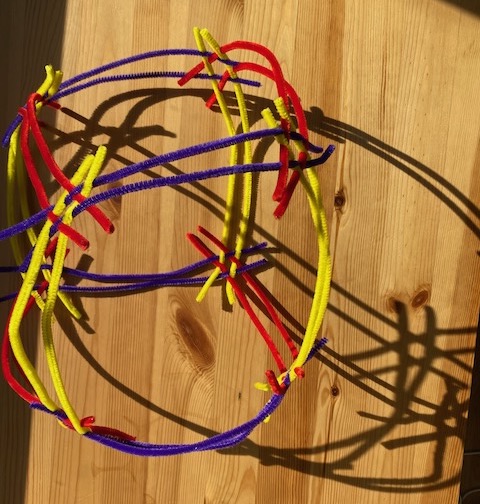

The tetrahedron is 4 of these vertices, spliced together exactly how you’d expect. If you’re a puritan about perfect weaving patterns, you can worry about the orientation of each vertex as you move around a face. This is inconsequential for the structure, since every vertex is already rigid. Still, the topology works out particularly nicely while weaving the cube. Here’s a pipe cleaner model.

|

|---|

| Model of the weaving pattern of a cube. Note how each vertex is a woven hexagon, in the same style as above. |

The same technique should work equally for any polyhedra with 3 edges per vertex.

Stick bombs or weaving?

Perhaps I’ve lost my way. With its long, flexible sticks, my tetrahedron feels less like the tightly-wound stick bombs from the intro, and more like the mathematical weaving exemplified by Alison Martin. Perhaps stick bombs and weaving are different ends of a spectrum, where stick bombs are made of highly elastic, short components. Perhaps stick bombs are weaving without any binding between the sticks – that’s what got me into this mess.

IMO, the moniker “stick bomb” is earned when thrown against a wall. Is my woven tetrahedron really a spherical stick bomb?

Looks like it.

Some food for thought: Despite two of the sticks falling out, the rest of the sticks stayed woven. In the language of this post, the stick bomb is not minimal. Can one design a woven polyhedra which entirely unravels when any crossing is removed? In other words, are there any minimal spherical stick bombs?

Construction process

It can be very frustrating to make things which want to explode, perhaps unsurprisingly. Let me say a bit about my construction process to light the way for any kindred spirits, be it the reader or future Elliot.

First I made a model so that I could see the topology. I used pipe cleaners (which are very forgiving), with different colors for each edge. It’s very easy to see which parts should go over and which should go under. See the pipe cleaner cube above.

I made my tetrahedron out of wooden coffee stirrers. These are cheap, accessible, and absolutely not the right material. They snap if the curvature is too high. Any spherical stick bomb has to be big, it can’t be desktop sized. There are two options. You can get longer sticks by gluing coffee stirrers together (wood glue works great), or you can make larger polyhedra. Here are the polyhedra I’ve tried:

- Single-length cube: No chance, the sticks snap.

- Single-length dodecahedron: Maaaaybe possible, but I couldn’t figure out the assembly. If you’re so bold, I suggest making the 10 vertices around the equator first, then adding the caps.

- Double- length cube: Same issue as the dodechedron. I couldn’t get it to bend out the plane without falling apart.

- Quadruple-length tetrahedron: It works!

Each vertex has 120 degree angles between the three incoming edges. Usually we manifest curvature by placing less than 6 vertices around a face. The 120 degree constraint requires things to pop out of the plane. However, the woven vertex, without any bindings, isn’t rigid! Here’s what happens when you try to make a cube, and attach 4 vertices together:

|

|---|

| The first step of making the cube. Note how the hexagons have 90 degree angles instead of 120 degrees. It has no issues laying flat. |

It’s still flat! This makes things a royal pain, because you now need to connect two edges which are pointing in almost oppisite directions. I got very close to a curved cube, but the sticks kept snapping. So I moved to the tetrahedron.

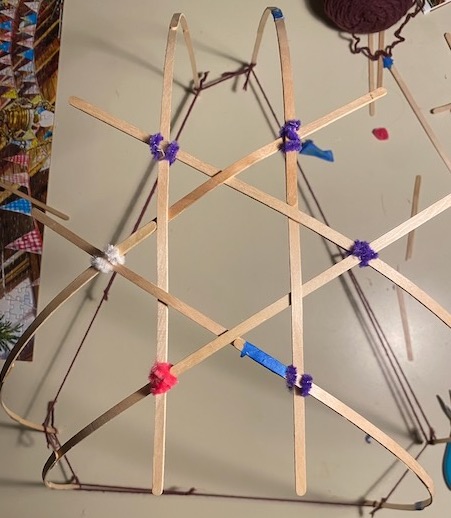

Here’s my approach. I started with a single vertex. I used pipe cleaners to (temporarily!) bind things together, so it doesn’t slide apart mid-bend (see below).

|

|---|

| Mid-construction picture. Note how the connections on the top are bound together using pipe cleaners, and how the sticks are pre-bent using string. |

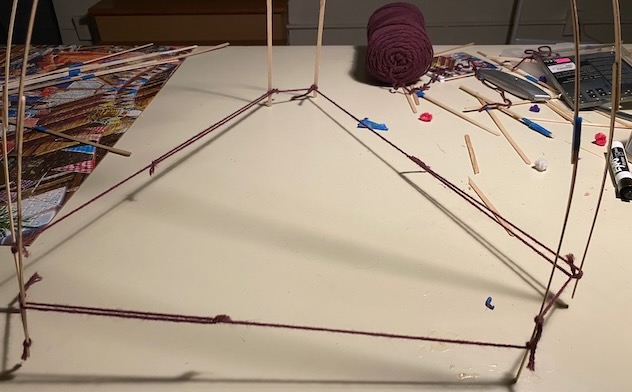

Next I pre-bent all three edges using string. I attached each edge to itself, so they don’t separate, then attached the three edges to each-other using adjustable knots. I tightened them to an approximate tetrahedron. You can see the top-down view above, and a close up view of the strings below.

|

|---|

| Another Mid-construction picture. Note how the strings used to bend the sticks have slip knots, allowing their length to be adjusted. The pairs of parralel sticks making up the edges are held at a fixed distance using string. |

Since the strings are holding things in place, its much easier to weave in the the remaining three edges. I noticed that, after my tetrahedron fell apart, the sticks kept their curve. It was much easier to reassemble them with the preexisting curve, I didn’t need to use the string at all. To make this as easy as possible,

My main suggestion: Pre-bend the sticks!

I don’t know the best way to do that. One way is to build the thing and leave it overnight like I did, but thats the chicken and egg paradox. You’re clever though, I’m sure you’ll figure something out.