Interlocking Paper Polyhedra

Summary:

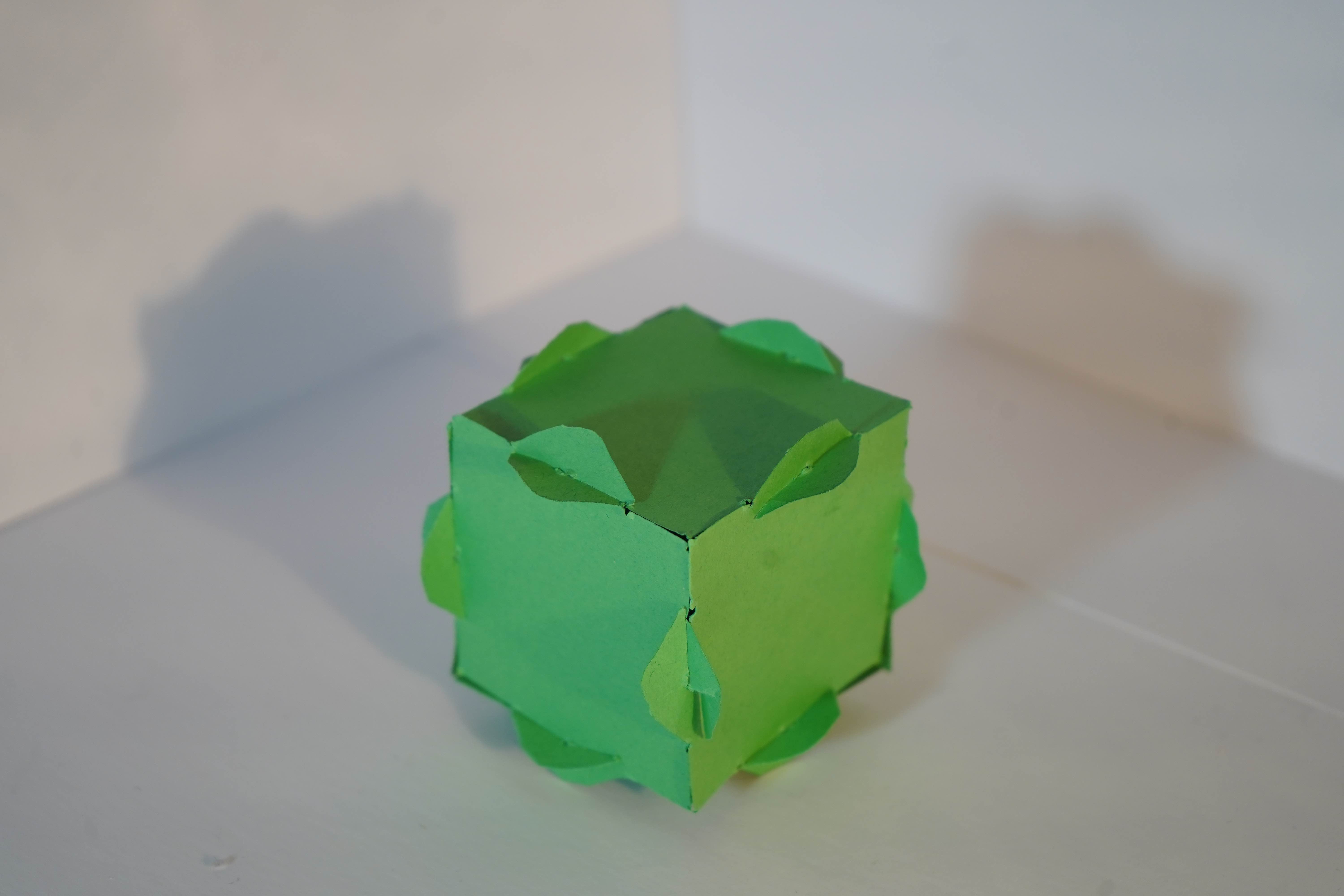

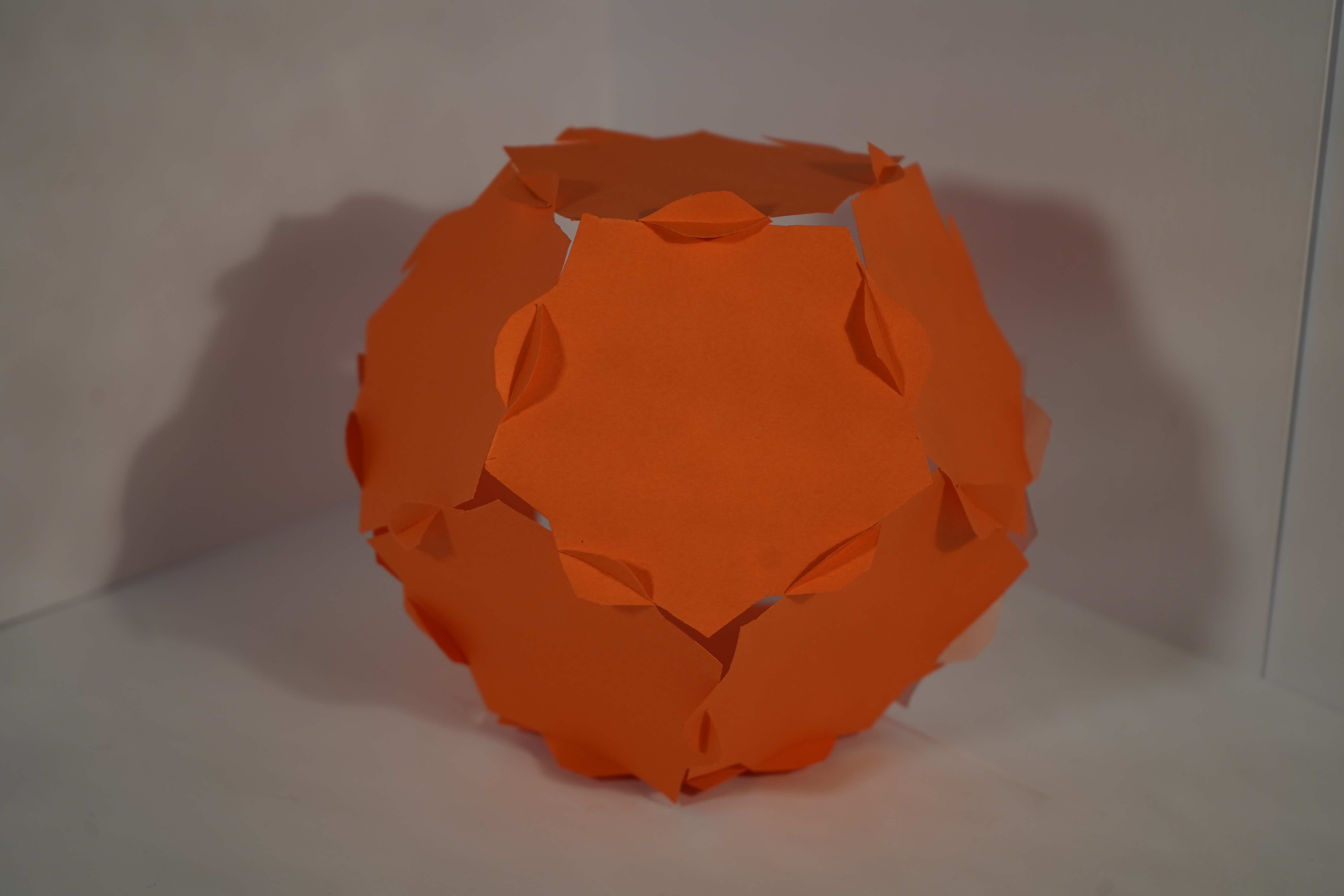

Craft: cut out slide-together polygons out of construction paper. Assemble these into polyhedra!

Math: Discover the platonic solids, and the rules governing what faces can fit together to make convex polyhedra. Study the angular defect around each vertex.

Summary

Welcome to math crafts! Today, we will follow the footsteps of the greeks before, and discover the platonic solids. Cutting paper into polygons and attaching them together, we can make a 3D object! The object’s shape is controlled by the number of polygons around each vertex – our first encounter with curvature. Just like the mathematicians of old, you won’t know the answers ahead of time. Instead, I’ll suggest questions for you to ask, and your explorations and curiosity will lead you ahead. You might not answer the original question, but you will understand something along the way.

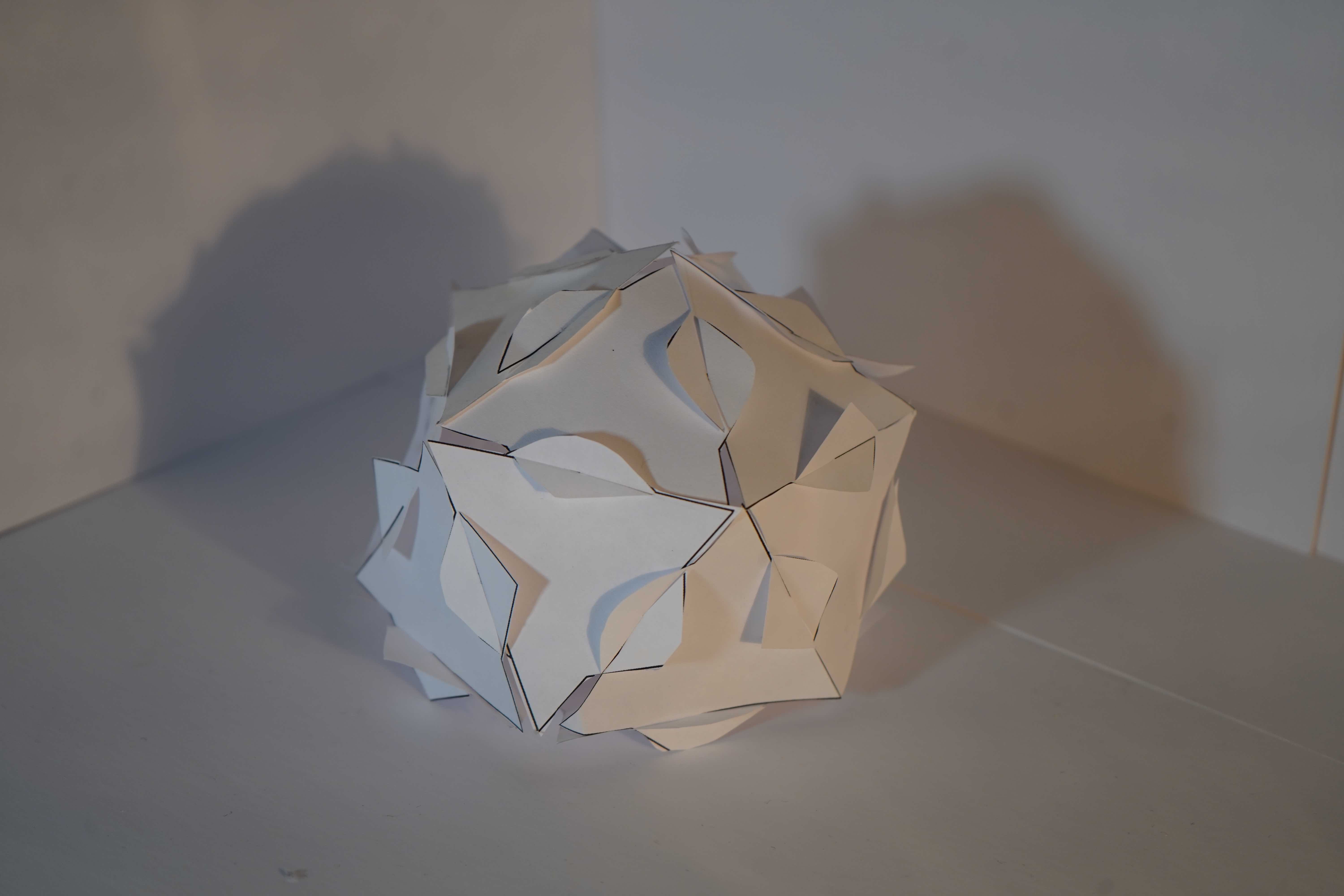

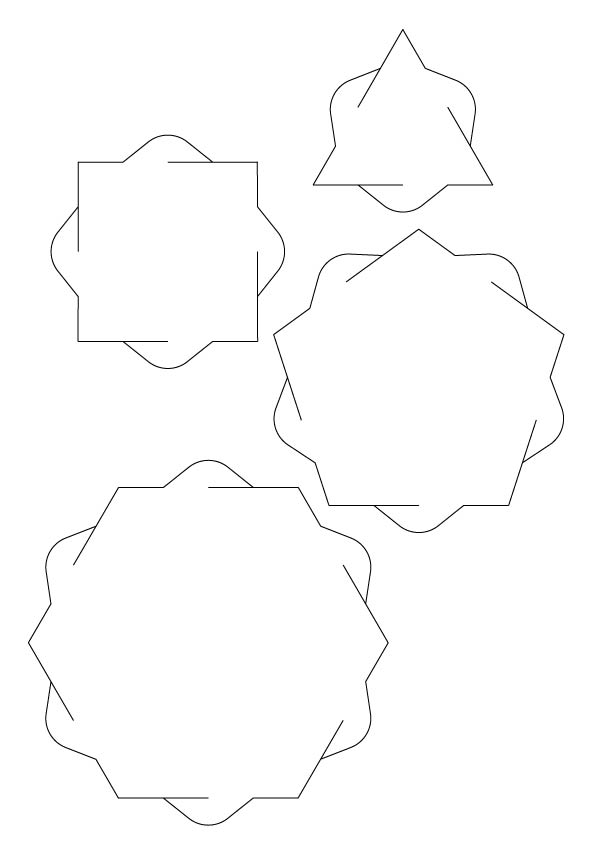

To make easy-to-attach polygons without tape or glue, we use interlocking paper tabs. I make some templates (see below), highly inspired by itsPhun. If you want heavy-duty plastic versions of these interlocking polygons, you can buy some there.

Materials and setup

Materials

Each table of 3 students will need:

- 16 sheets of 65lb cardstock (details below)

- 3 Scissors

It will be good to have on hand for the class:

- a protractor or two

- tape

Setup

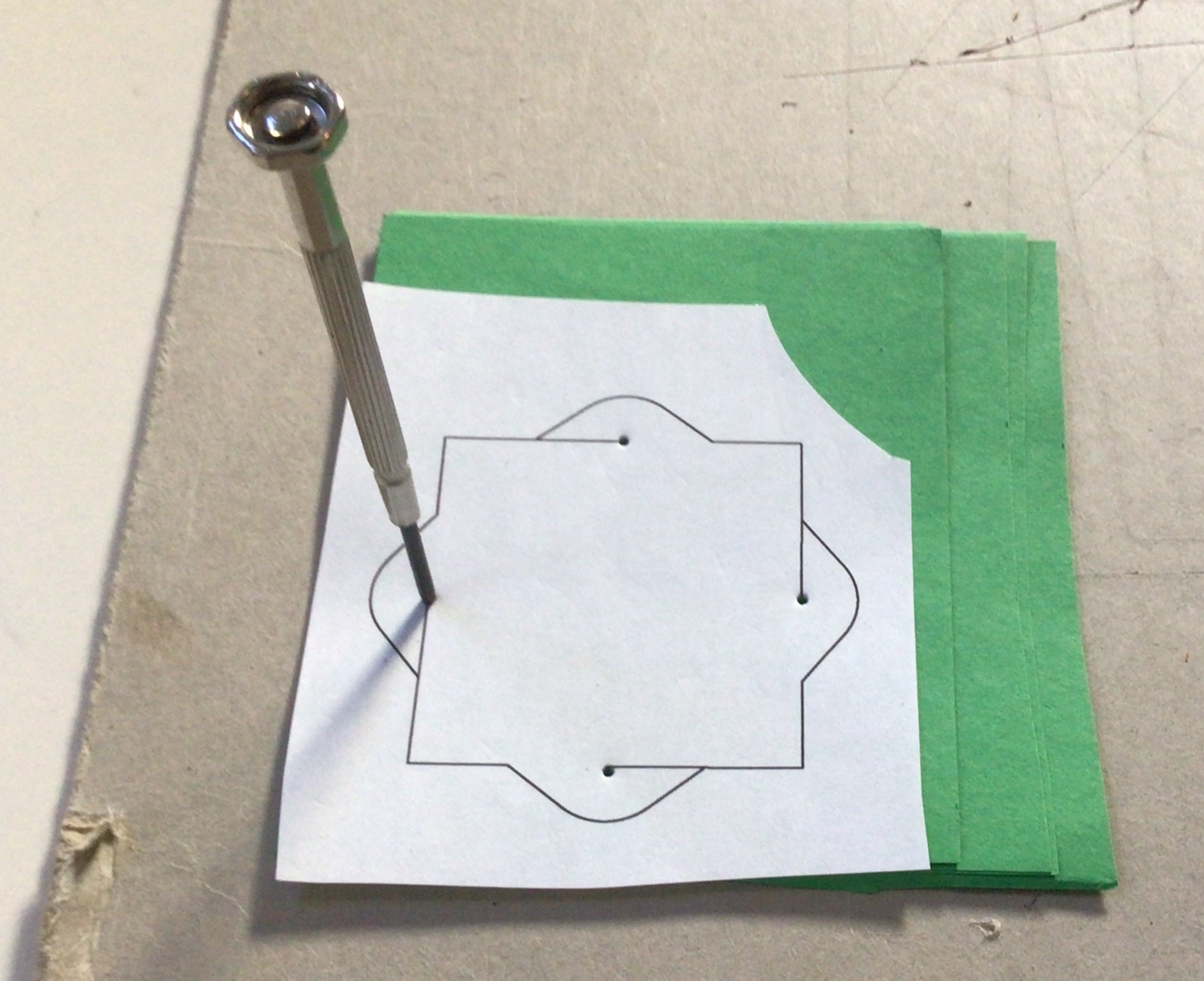

We will have the students cut out the paper polygons using the templates below, which look like the picture above. Precision is important, specifically for the cut that ends halfway through the tab. Cutting through a stack of papers with scissors and a template gives rather unsatisfying, shoddy results. With a little prepreperation, things go more smoothly. We will use a trick inspired by George hart. Place a template above a stack of construction paper or cardstock, all atop a scrap piece of cardboard or two. Then, hammer a nail through all the layers at essential points of the template: The endpoint of the slit (Important to get this precise!).

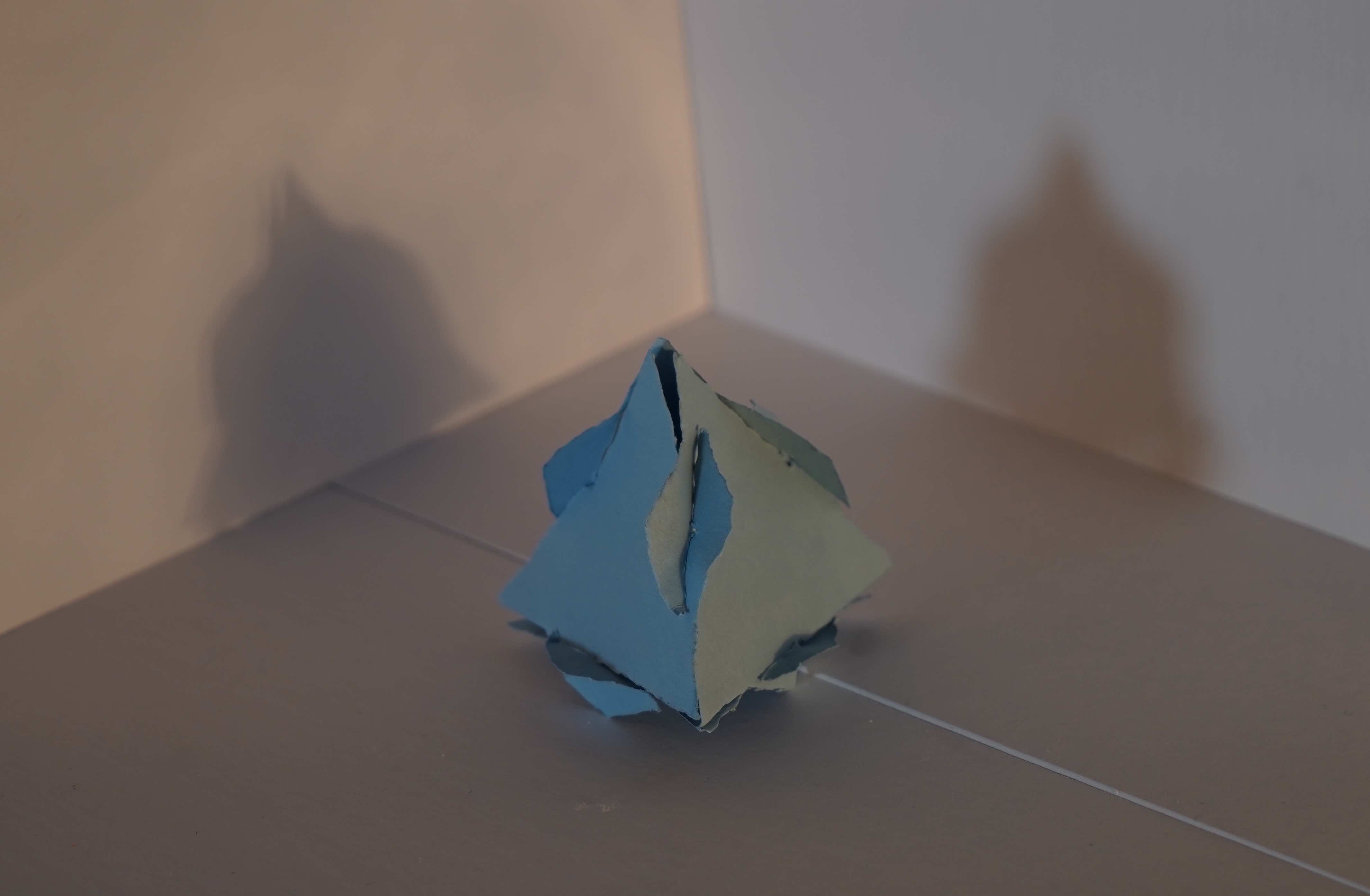

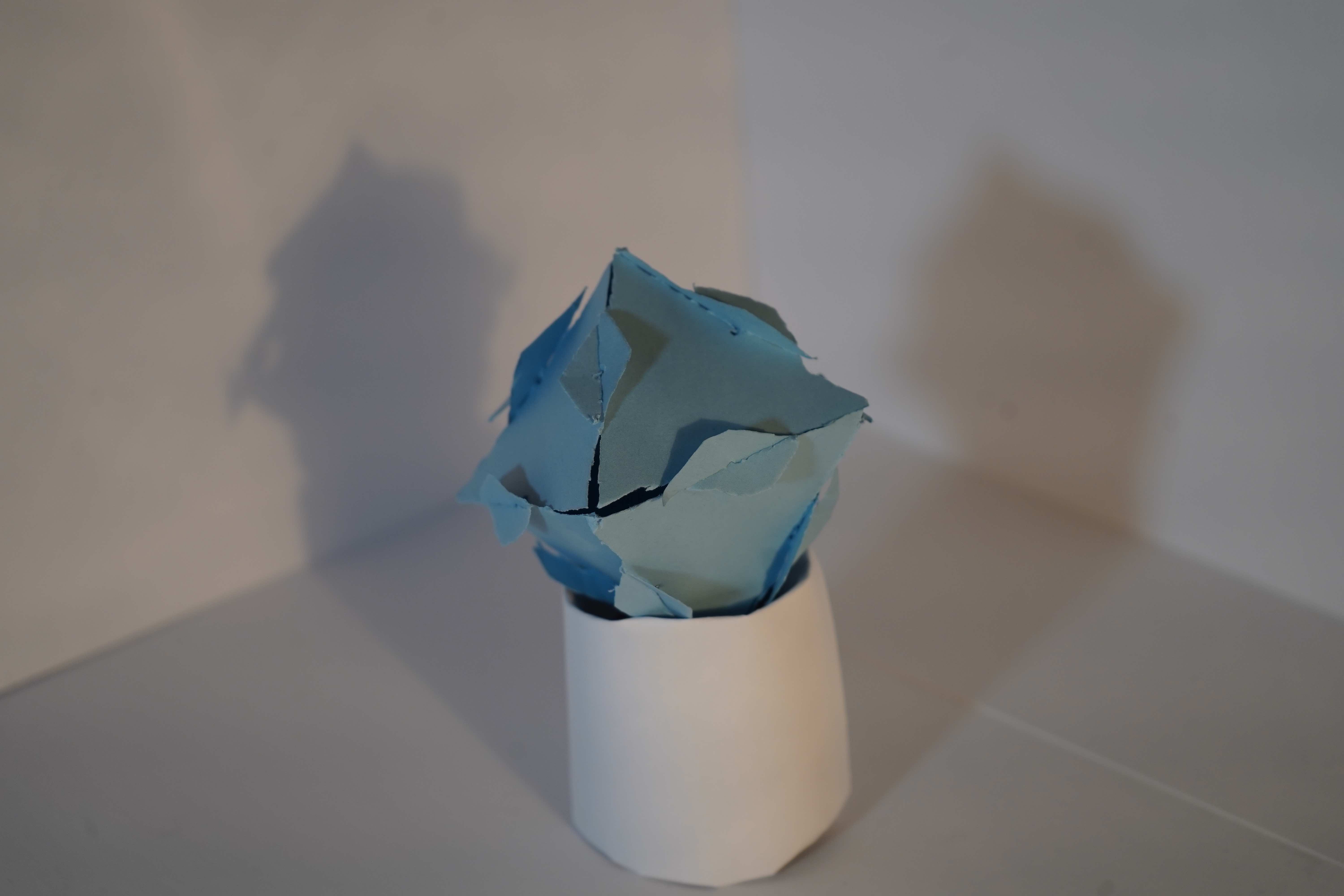

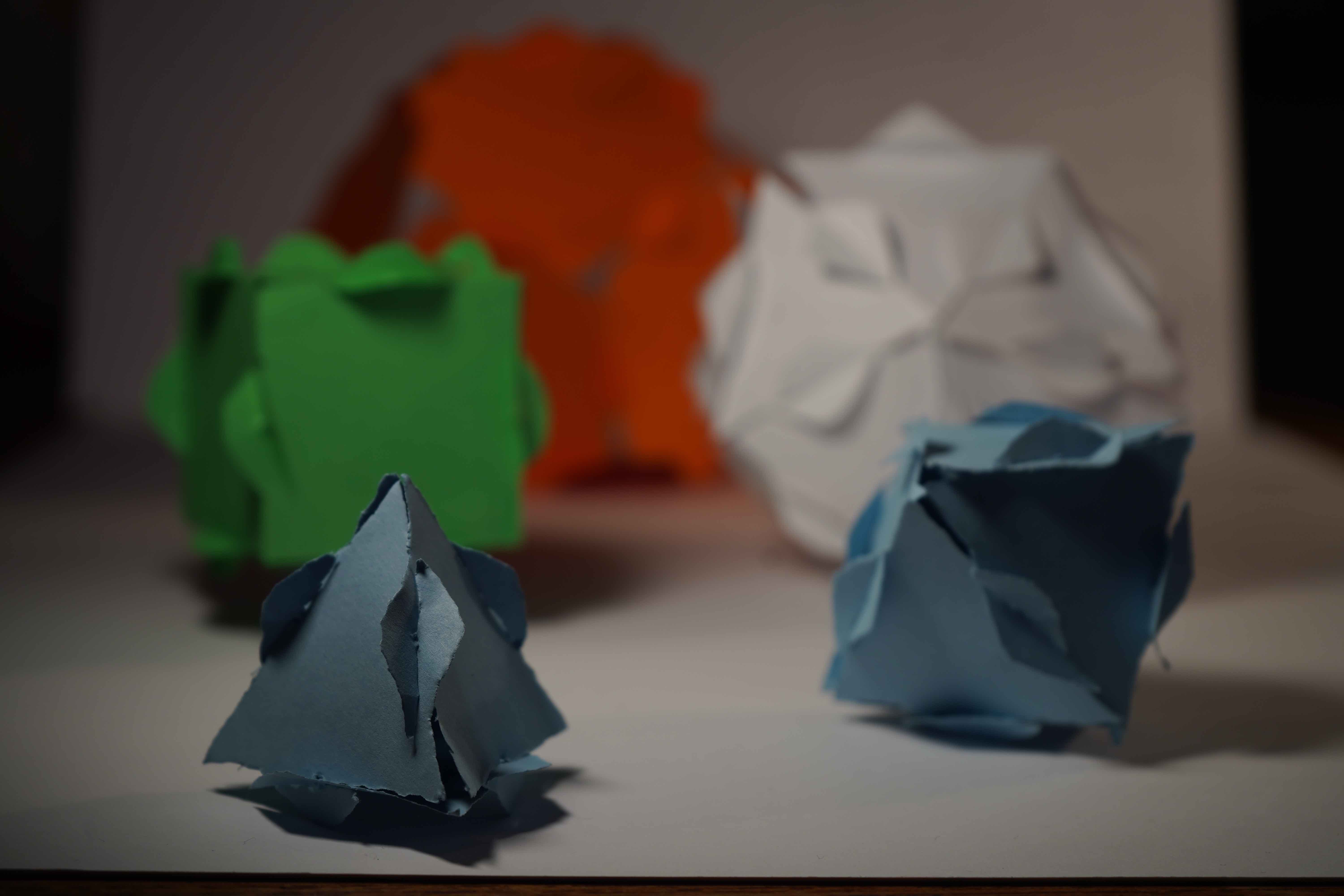

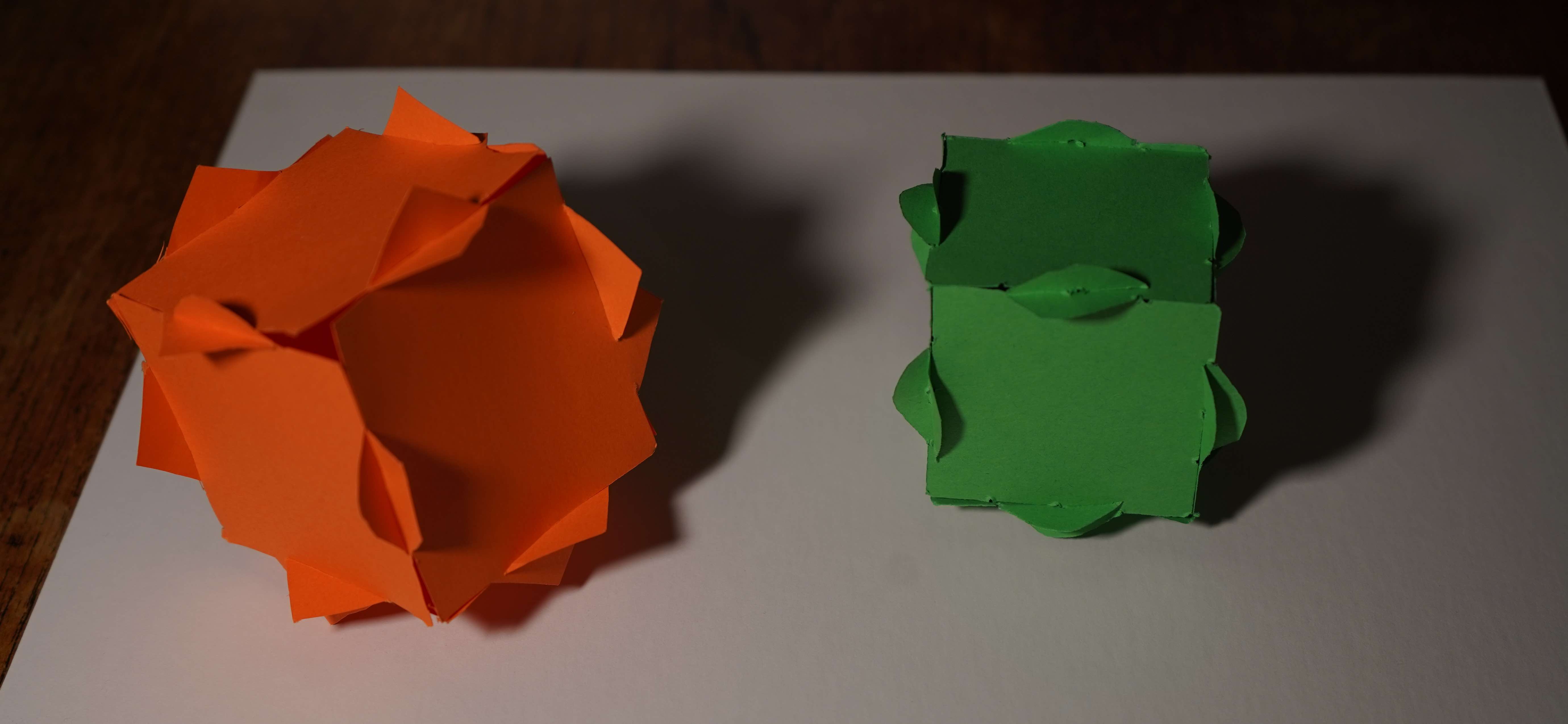

This has a few benefits: The nail holes hold the paper aligned together. This makes it easy to hand out whole stacks of paper, and lets the students cut the whole stack at once. They just need to cut to the holes, helping their percision. Also, the scraggly nail holes hold the tabs together quite well. Compare the build quality below: Left is without nails, right is with nails.

I organize my students into tables of 3. For each table, make:

- 1 2-hexagon template

- 1 4-pentagon template

- 1 8-square template

- 1 12-triangle template

Place each of these over a stack of 4 sheets of cardstock. Ideally keep all of each shape the same color across the class. I used 65 lb cardstock, which has a good heft with some longevity. If you only have construction paper or lower weight stuff, it should still work, but will be more flimsy. I’d be cautious about heavier cardstock: 4 sheets was already pushing the limit for the cheap class scissors. With heavier stock, you need less per stack if you want clean cuts.

In total, I had 4 groups. This came out to

- 64 sheets of cardstock paper

- 4 of each template

This comes out to 380 total punches. This took me about 1-1.5 hours– it goes by quick once you get a rhythm.

Templates

Here are the templates. Printed on US-standard *1/2 - 11 paper, these give polygons with edge length 1.5 inches. These are oriented for right handed cutting convenience, if you’re left handed its convenient to flip the template.

- 12 triangle template

- 8 square template

- 4 pentagon template

- 2 hexagon template (this has two extra triangles to not waste paper)

- All polygons together

If you’d like to edit these templates or laser cut them or something, here’s the vector file:

Platonic solids

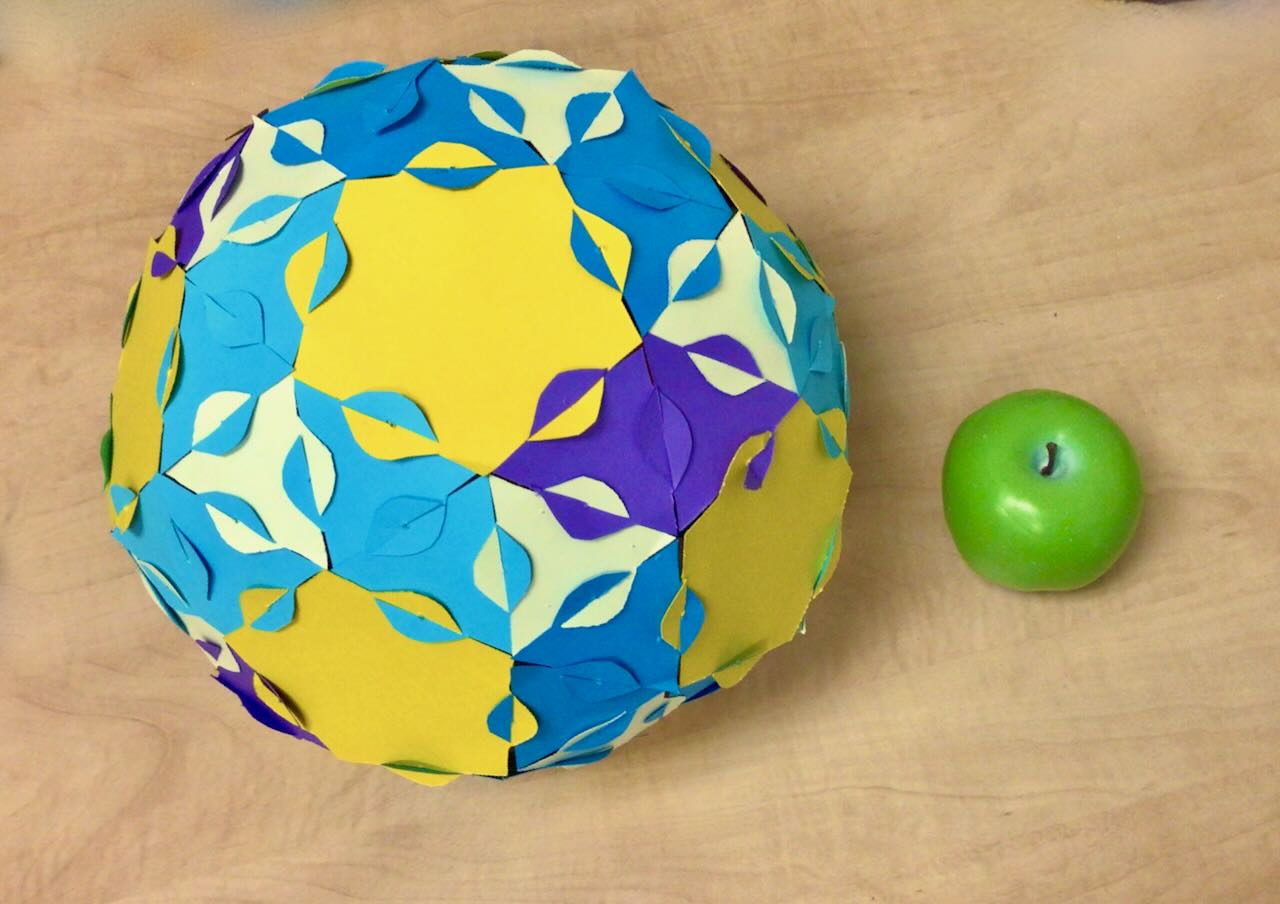

Today we will make some balls. Like soccer balls. These are made by sewing together white hexagons with black pentagons, and inflating. We will do the same, using interlocking paper instead of sewen leather. Demonstrate by creating the tetrahedron on front of them)

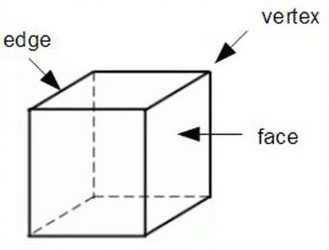

For us to talk about these questions together, we need a common language for 3D shapes. Today we’re only going to think about shapes made of flat sheets attached together. These are called Polyhedra. The flat parts of the polyhedra are called faces. Each of these is a 2 dimensional shape (a polygon). The boundary of each face is a collection of one dimensional line segments called edges, and the corners of each face are points called vertices.

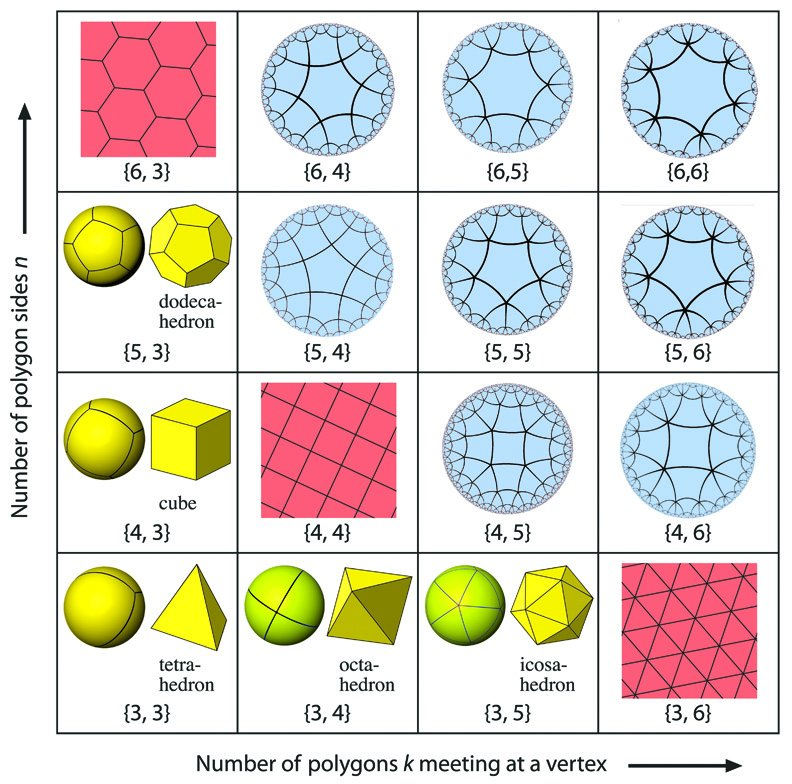

Understanding check: How many faces, edges, and vertices does a cube have? (pictured above)

We make two groupd rules:

- All faces the same

Each face must be a regular polygon, and you’re only allowed one type of polygon.

- Each vertex has same composition

The faces around each vertex must be the same. For example, the tetrahedron has 3 triangles around every single vertex. This keeps our balls symmetric

Question 1: Build as many platonic solids as you can think of. Once your table makes a solid, have someone write its name on your table’s whiteboard. How many could you find? How many faces does each have?

Question 2: I have another name for the octahedron: I call it the $\{3,4\}$-hedron. Likewise, I call the tetrahedron a $\{3,3\}$-hedron. Can you guess what a $\{p,q\}$-hedron means? Can you name all your other polyhedra?

As mathematicians, once we discover something, we need to give it a name – how else can we discuss it with one another? Come up with names for the platonic solids you’ve made. Try to make it so someone who just knows the name could figure out how to build the shape. (if you already know names for these shapes, can you come up with better names?)

Question 3: Are there any other platonic solids you haven’t built? Can you prove there are no more?

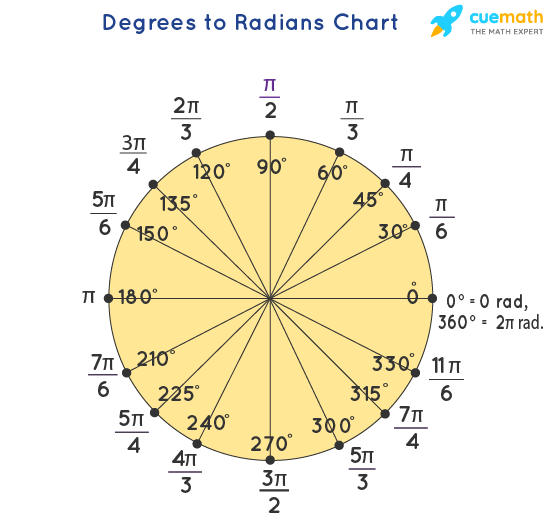

Hint: Think about the angles around each vertex. Here are the angles for each regular polygon, measured in radians. There are a total of $2 \pi$ radians in a circle.

| number of sides | angle |

|---|---|

| 3 | $\pi/3$ |

| 4 | $\pi/2$ |

| 5 | $3\pi/5$ |

| 6 | $2\pi/3$ |

| $\vdots$ | $\vdots$ |

Question 4: You should have found a platonic solid with 5 triangles around each vertex. What happens if you put 6 around a vertex? 7? (you might want to cut off the tabs and use tape for 7 or more).

Likewise, what happens when you put 4 squares around a vertex? 5?

Can you determine a rule which relates the behavior of a vertex to the angles of the faces surrounding it?

Question 5: Platonic solids are pretty restrictive, so let’s break some rules. What shapes can you make that follow rule 2, but not rule 1? That is, there are multiple types of faces, and each vertex is surrounded by the same combination (say, two triangles and two squares per vertex). These are called archemedian solids

Construct a few different archemedian solids. Calculate the angle defect (2 $\pi$ - total angle) around each vertex. Is it positive, negative, or zero?

Are there any archemedian solids with 3 different types of faces? 4?

Class activity

For the last 20-25 minutes: First, synthesize and give answers for all the questions above. When you talk about archemedian solids, hold up examples from the class and name them with math words (people like that). Explain how they are constructed, if you can. For example, the cuboctahedron is formed by cutting off the corners of the cube, and similarly for the icosidodecahedron. This got me some A-ha moments.

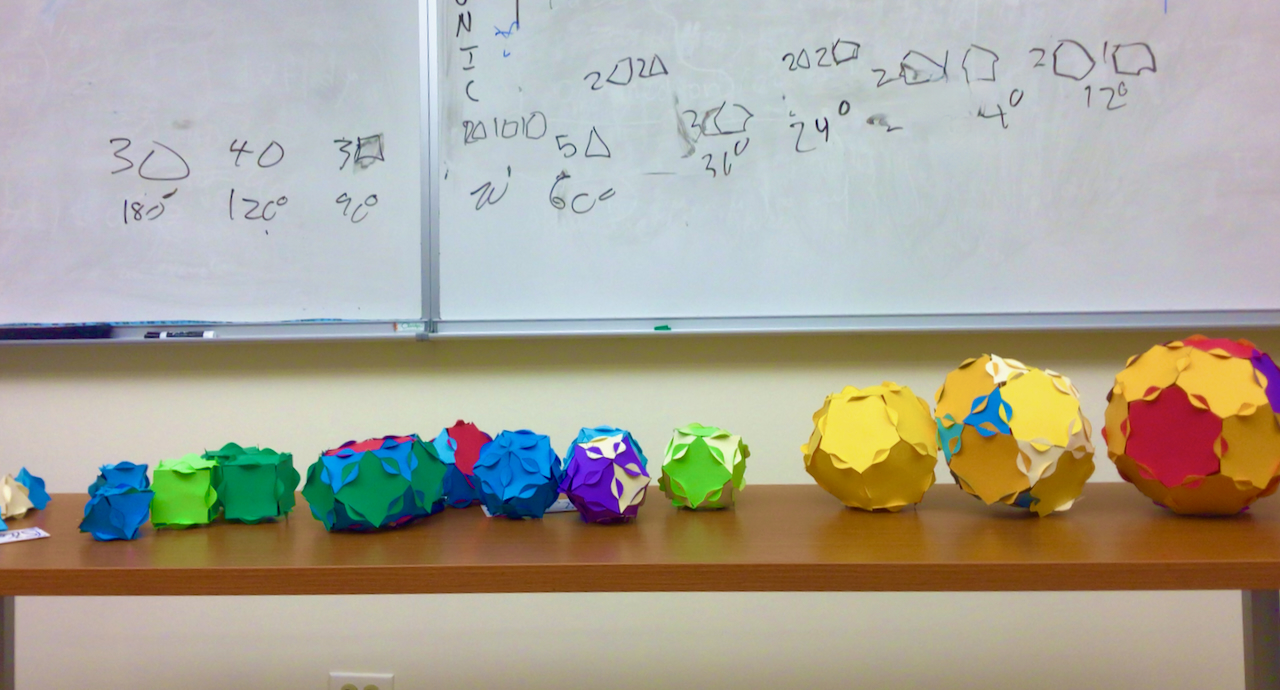

Then, designate one table as the display table. Have people calculate the angle defect for each of their polyhedra. Have them place it on the table, in order from largest to smallest, and write in dry erase marker on the table the schaflies symbol and the angle defect. Students should notice that the smaller the angle defect, the larger the shape. Explain how angle defect controls curvature, and the more tighly curved the sphere is, the smaller it must be. We will see more examples of this later in the course.