Hyperbolic origami

Summary:

Craft: Create origami models of hyperbolic space.

Math: examine how to approximate negative curvature using zero-curvature paper. Understand negative curvature as an excess of space, and as a deficet of angles.

Summary

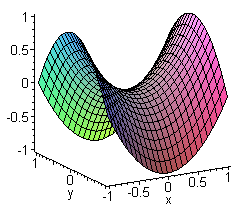

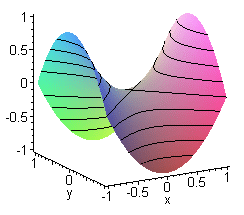

Last class we introduced curvature of a curve in 2D, and described how to measure it quantitatively. This time, we use 2D curvature to define the curvature of a surface in 3D. This is called “Gaussian curvature”, and it will be our primary way to understand curvature in this class. We start with a simple origami model of a hyperbolic paraboloid, affectionately called a “hypar” by origamists. The same principle applied to simple, circular creases creates a beautiful sculpture.

Materials and setup

materials and setup

Every student should have:

- 1 box cutter. I found a pack of 24 on amazon for 10 dollars

- 1-2 of each type of template (see below), 4 total. I used construction paper

In total, for a class of 12, I printed 20 of each template.

Templates

worksheet

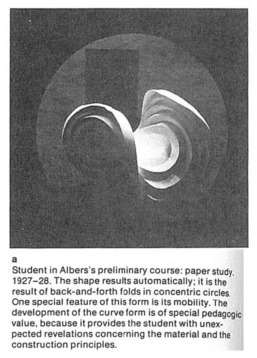

History of curved origami

Though origami is an old art, it is rare to have written sources of origami patterns from long ago. Most sources are not much older than the 1980s, when a modern origami renaissance was spurred by mathematical design principles. People just didn’t right down very much. The two models above are the exception which proves the rule. Both the hypar and the curved sculpture have sources dating back to a paper study class taught at Bauhaus in 1927-1928.

Bauhaus was a german (physical) art school that inspired a (metaphorical) school of design. its followers prized simple geometric shapes and held an artistic reverence for function. The origami sculptures show Bauhaus principles quite well. The professor Josef Albers lead class with an incredible speech, here retold by one of the students:

I remember vividly the first day of the [Preliminary Course]. Josef Albers entered the room, carrying with him a bunch of newspapers. … [and] then addressed us … “Ladies and gentlemen, we are poor, not rich. We can’t afford to waste materials or time. … All art starts with a material, and therefore we have first to investigate what our material can do. So, at the beginning we will experiment without aiming at making a product. At the moment we prefer cleverness to beauty. … Our studies should lead to constructive thinking. … I want you now to take the newspapers … and try to make something out of them that is more than you have now. I want you to respect the material and use it in a way that makes sense — preserve its inherent characteristics. If you can do without tools like knives and scissors, and without glue, [all] the better.”

I started class with this quote. For more on the history of curved origami, see Erik and Martin Demaine’s webpage

Part 1: The hyperbolic paraboloid

Fold the hyperbolic paraboloid in the handout. (courtesy of Thomas Hull’s book Project Origami)

Question 1: squint your eyes, think about the surface approximated by the corrugated, folded paper. What is the gaussian curvature at the center? What about at another point?

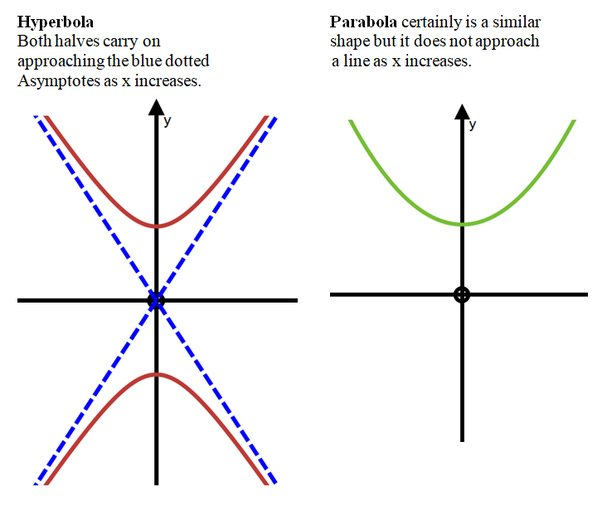

Question 2: This shape is close to something called a hyperbolic paraboloid. This is named after two shapes: the parabola and the hyperbola (shown below). Can you find two hidden parabolas inside the origami you just made? Can you find a hyperbola?

Question: 2a Last class, we saw that a sheet of paper, no matter how it is bent or folded, always has zero gaussian curvature. Yet, we have made something with nonzero gaussian curvature. How is this possible? What changed? (This is a subtle question. Talk about it a few minutes before moving on.)

Question: 2b Fold the hypar to its most extreme position, bringing its tips together. Are the paper faces flat? Are there any parts of the hypar where the paper looks particularly bent out of shape? What about in less extreme positions?

We see now that something is up with the hypar. In fact, the hypar is fundamentally hyperbolic. The curvature arises because the paper has too much perimeter for its radius, forcing it to pop out of the plane. Let’s see this is detail, first by understanding the perimeter of squares on the euclidean plane.

Question 3a: Using a ruler, measure the perimeter and radius of your hypar. If you’re comfortable with geometry, consider a square on the plane, centered on the origin, with distance to the origin $r$. Write a formula relating the perimeter of the square in terms of $r$.

Question 3b: Now we corrugate the paper, by folding it into the hypar pattern. What happens to the distance from the edge to the origin? What happens to its length? Using a ruler, what is the new perimeter and radius? Can you use this to explain curvature?

Question 4: Have one member of the table cut out the central square of the hypar. Compare the holey hypar with the filled ones. What happens when you squeeze two opposite ends together for both holey and filled hypar?

Remark: Hyperbolic paraboloids and curvature

I’ve only told you about two parabolas, which are the most extreme parabolas: They are the directions of principle curvature. In fact, there are infinitely many other parabolas. Restrict to a two dimensional plane twisted by an angle theta (paramertized by $\cos(\theta) x + \sin(\theta) y = 0$). The graph of $z=x^2 - y^2$, restricted to this plane, the graph looks like a one dimensional graph $z= k(\theta) x^2$, for some constant $k$ depending on the angle $\theta$. In fact, $k$ is exactly the curvature of the curve at the origin. If one does out the algebra, she would find that $k(\theta) = \cos(2 \theta)$. This is a sinusoid, so its value at any angle is entirely determined by its largest and smallest values. Let’s see some examples:

- When $\theta=0$, $k=1$ so the parabola points straight upwards.

- When $\theta = \pi/2$, $k=-1$ and the parabola points downwards.

- When $\theta= \pi/4$ or $\theta = 3\pi/4$, $k=0$. This corresponds to a flat line, which happens along the diagonal lines of the origami square.

Now suppose we examine the curvature of a point on an arbitrary surface, one with negative curvature. We can study this using our trusty hypar. By squishing and moving the corners of the paper, we can make the hypar approximate the surface near that point. This will change how tightly the two main parabolas are curved. Then, the curvature of the surface sliced by a plane is entirely captured by the curvature of the hypar. For example, the two main parabolas of the hypar control the principle curvatures of the surface. In particular, as the angle of the plane varies, the curvature of the slice also varies sinusoidally. Using properties of sinusoids, We’ve discovered:

- The curvature at any angle is entirely determined by the two principle curvatures.

- The two principle curvatures must occur at 90 degrees relative to one another.

This explains why principle curvatures are so principle, and why gaussian curvature captures essentially everything we need about a surface. Secretly, we’ve just applied a central idea of calculus: Every function and shape is well approximated by polynomials, in this case a second order functions. After all, our hyperbolic paraboloid only used $x^2$ and $y^2$. Following the themes of calculus, the particular coefficients in our best approximating polynomials tell us how fast our function is changing – in this case, it measures the principle curvature.

Wrap up activity: Any people who don’t want to keep their hypars should bring them to the front. There, we can put them together using tape to build a large amalgamated sculpture. See here for examples, choose whichever you have enough hypars for. Anyone who finishes the whole project early can help assemble the sculpture

Part 2: Curved origami

The heart of last construction was the alternating concentric squares, each with mountian/valley folds. We can make a visually pleasing version using concentric circles instead, though this requires some creative creasing. In contrast to the hypar above, we will call this origami shape the hycircle

Instructions for the Hycircle

Get the following materials:

- A box cutter / craft knife

- A piece of cardstock

- A spare piece of cardboard to cut on

- A thumbtack

- A piece of string

- A pencil

- (optional) A ruler of some kind.

instructions

- Setup the paper on the cardboard, held with the thumbtack in the center of the paper. Tie one end of the string to the thumbtack.

- By tying the pencil some length along the string, we can draw circles on the cardstock. Produce several equally spaced, concentric circles. You can choose any parameters you like, but I’d recommend the following:

- Make the largest circle as large as possible – larger is more ambitious

- Use a 1 cm change of radius between each circle – Smaller spacing is more ambitious

- Make the smallest circle ~ 1/2 the radius of the larger one. This is not so important, and can always be increased later.

- Cut out the pattern using the largest circle.

- Flip over the paper and repeat the markings ==can I get away without this?==

- On every other ring, score lightly with the box knife. do not go all the way though. This will force the paper to curve where you cut.

- Flip the paper over again, and score on the rings not already scored on the other side

- Cut out the innermost ring

- Make all the creases, going around and pinching to encourage the paper to fold along the circles in the direction dictated by the scoring.

Question 5: Measure the difference in radii between the inner and outermost circle of the flattened hycircle. Then, corrugate the hycircle, and measure the new difference in radii. How does the radius change? How does the perimeter change? Using what you know from the square case, how does this induce curvature?

Question 6: What configurations can you move the hycircle into? Try turning it “inside out”. Compare this to the feeling of hyperbolic folding cardboard from the earlier week.

Wrap up: Fit today’s activity into these themes of the class:

- Negative curvature makes things Bigger than expected

- Negative curvature makes things Flexible

sources

Curved Crease Folding a Review on Art, Design and Mathematics by Erik D. DEMAINE, Martin L. DEMAINE, Duks KOSCHITZ, and Tomohiro TACHI

- compendium of original sources of curved origami, and its applications to math and design.

More on Paperfolding By Dmitry Fuchs and Serge Tabachnikov

- Differential geometric description of paper along curved folds

(Non)existence of Pleated Folds: How Paper Folds Between Creases, by Erik D. Demaine, Martin L. Demaine, Vi Hart, Gregory N. Price, Tomohiro Tachi

- Proves the hypar is impossible with straight edge creases and no bending. Discusses how elasticity forms the hypar crease pattern into a hyperbolic paraboloid.

instructions for curved origami

Gallery

folded hyperbolic paraboloid

A hyperbolic paraboloid, folded from a square. This is a classic bit of origami, helped along with some pre-creasing. For details on its construction, see the page above.